| Welch, T (November 1999) 'Evaluating the quality of assessment practices in

teacher development programmes: Lessons from the Educator Development and Support (EDS)

Project 1999'

in SAIDE Open Learning Through Distance Education, Vol. ?, No. ?, SAIDE:

Johannesburg |

|||

| South Africa | Contents | ||

By Tessa Welch

Introduction

The purpose of the EDS project was to contribute to the EDS standards-generating process in the Schooling subfield of the Education, Training and Development field Through ten case studies of EDS programmes, the project tried to record current understanding of and practices in EDS, to examine these in the light of the recommendations offered in the Norms and Standards for Educators report1 and other key policy initiatives, and to understand through the research activity:

How the EDS standards-generating process can be further developed;

How in general rather than programme specific terms the design of EDS programmes can be improved;

How the Norms and Standards for Educators (NSE) report can be refined and further elaborated2.

The purpose of this article is to focus on the assessment requirements in the NSE report and how distance teacher development programmes responded to these. If the NSE report is regulated, the evaluation of programmes will have to be undertaken at least in part in terms of its criteria.

Assessment practices in distance teacher education and the NSE report

The Norms and Standards for Educators report says that the assessment practices of a programme must be applied and integrated. That is, the programme must assess the extent to which learners are able to integrate the knowledge and skills delivered through the different courses/modules that constitute the programme (horizontal integration). In addition, the assessment practices of a programme must be so designed as to permit the learners to demonstrate practical, foundational, and reflexive competence, and must assess the extent to which learners are able to integrate these competences. Integrated and applied assessment must be ongoing, developmental, and contextualised. Teachers need to be assessed on how they are able to perform their teaching functions in authentic South African contexts.

This raises certain questions, particularly for distance education providers. Recorded below are the more interesting questions and findings from three of the distance education case studies in the EDS project:

A: large scale distance education

programme (public/private partnership);

B: a mixed mode programme offered by a university;

C: a mixed mode programme offered by university and NGO collaboration.

Question 1: How does the integration of foundational, practical, and reflexive competence translate into assessment design? Is application the same as integration?

Integration of the three dimensions of applied competence appears to be problematic for programmes.

Staff of Programme A seemed to suggest that a written question giving practical applications was what was required in integrated assessment:

"Assignment and exam questions are phrased to assess both a learner's understanding of concepts, methods and principles of a particular subject course, and the application of these. Typical questions require students to clarify concepts, or as the following example taken from the course illustrates - Explain why schools should be viewed as open systems. Make use of the following model and describe each of the components briefly. Supply a practical example for each component3."

Programme C staff said that they tried to conduct integrated assessment by placing staff in schools to help the teachers reflect on their practice. But this was not sustainable from a funding point of view. Therefore the programme now focuses on foundational competence, and to some extent on practical competence, but does not have a conscious strategy to deal with the assessment of reflexive competence.

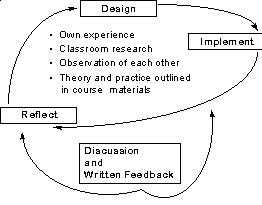

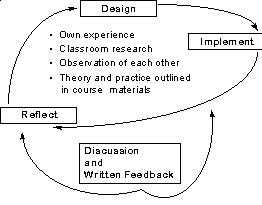

Programme B appeared to integrate the assessment of practical, foundational, and reflexive competence in the design of written assignments for one of the courses focusing on subject teaching knowledge and skills in ways illustrated in the following diagram4:

Assignments for other courses in this programme did not follow this pattern. For example, certain of the subject knowledge courses needed assignments that helped students practice and demonstrate conceptual understanding.

What seemed to emerge overall was that while it was reasonable to expect the programme as a whole to integrate the three dimensions of competence in at least some of the assignments, it was not reasonable - because of the difference in subjects - to expect such integration in every assignment. The programme needs to demonstrate that it assesses applied competence (rather than merely the ability to apply theoretical concepts), but it can do so in a variety of ways.

Question 2: Can written assignments be used to assess practical teaching/management competence? Often the goals of teacher development programmes indicate that practical competence will be developed, but is it possible to determine practical competence from written assessment only?

The case study report on Programme A said that inherent in an integrated and applied assessment approach is the assumption that assessment criteria must be derived from the purpose of the qualification. The purpose of the programme was expressed as follows:

To develop the intellectual and practical skills of a learner to be competent as an Education Manager (including inter alia school and classroom management).5

However, the report writers said that the emphasis on written forms of assessment calls into question the extent to which the programme is in fact able adequately to develop and assess the practical skills.

Programme C developed this argument by distinguishing between the measurement of practical competence as outputs - in which a written response was acceptable or as outcomes - which required the observation of behavioural change.

Programme C staff also raised the problem that certain kinds of practical competence require demonstration at a systems level, but teacher development programmes tend to focus on students as individuals:

"In addition to the difficulties related to the subjective assessment of practical competence, the assessment of learners that have been trained as individuals, coupled with the expectation that they demonstrate practical competence at a systems level, is problematic. The question posed is therefore whether it is possible to provide skills training to learners as individuals, and then observe them in systems to demonstrate practical competence?"6

What emerges from this discussion is that, at the very least, programmes need to reflect honestly the nature of the competence that they develop and assess, and more particularly how they understand practical competence.

Question 3: Does the demand for integrated assessment in authentic contexts mean that it is necessary to assess students' teaching in their schools or at the kinds of schools in which they might teach?

This question is clearly related to the previous one, and implies that practical competence can only be assessed fully (as outcomes, or as an ability to work in a system) in a context similar to that in which the teacher will ultimately practise the competence.

In Programme A, no observational assessment in schools was conducted. However, the notion of 'authentic context' was understood in an interesting way. It was clear that staff understood the context of the learners and design questions that are authentic to that context, but they do not assess in the authentic context:

"I think we covered that [the issue of authenticity] to some extent in our work sessions at [our centre] where they [students] come with a problem. Then we just make notes, so that we can give them a similar kind of situation, which is authentic or similar to situations in their schools, in assignments or exams.

In- or un-authentic, for me, would be to take material directly from an Australian, American situation, or even if say you have a picture of an ex-model C school in your mind, when you're planning a course, and it has no relevance to your students".7

Programme C said that school-based assessment is an ideal for which to strive, but said it had not been possible for the programme to sustain this because of the vast amount of resources that are required. Programme C staff also highlighted the unreliability of school-based assessment:

"Implementing assessment in an authentic context implies that there has to be a strong element of trust in the relationship between the learners and the 'system'. Programme team members believe that the element of trust is missing the relationship between programme providers and learners, and hence it is difficult to creatively combine summative assessment and formative development approaches in an authentic context."8

What Programme C staff also mentioned was that even though school-based assessment was not part of the assessment of every student, some school-based observation and research was undertaken to ensure that staff were aware of how the programme was impacting on the teachers.

Programme B has also not undertaken assessment of students' teaching competence in situ, but assesses applied competence at the level of 'output' rather than at the level of observed behavioural change.

I would like to argue that it might be inadvisable to insist upon school-based assessment for every student on a programme. Even in preset face-to-face colleges where students do teaching practice in local schools, the organization of teaching practice is often not effective.

It is difficult to ensure that tutors interpret criteria similarly. Tutors usually observe a proportion of lessons outside their area of expertise, and often see particular students for no more than a single lesson. Tutors are often not involved in the planning process giving rise to the lesson they observe. They are also usually unable to see whether the student has been able to make use of their comments in the improvement of subsequent lessons.

In other words, even though students' practical competence is being observed in an authentic context, the assessment is not integrated. Tutors cannot judge teaching as a process of developing competence - it is usually observed as a once off display. It would much more sensible and helpful to the students if providers concentrated more on creating opportunities for students to acquire competence than on creating opportunities to assess it in authentic contexts.

Question 4: How much assessment is necessary to constitute an ongoing developmental approach?

In the case studies conducted for the Educator Development Support Project, a worrying trend in large scale distance education programmes were the paucity of assignments (in one case, assignments were voluntary, in another there was only one assignment per course) leading to:

"reliance on summative assessment practices to determine a final result, the lack of opportunities for students to present draft assignments, the lack of systematic feedback to learners on examinations and assignments".9

In Programme A, even though a number of assignments are written across the different courses, the lack of integration across courses means that students are effectively assessed twice for each of the courses - an assignment followed by an examination.

In Programmes B and C, ongoing developmental assessment was understood in terms of numerous assignments with extensive feedback. In the case of Programme B, there were at least four assignments per course for each of five courses. As was commented about in research done for the President's Education Initiative10:

It is important that students are required to go through the same processes again and again as it gives them an opportunity to develop broader abilities over time rather than merely master the content of individual units one by one. Furthermore these broad abilities are central to the successful teaching of reflective practitioners.

If distance education is going to exploit its potential for individualised teaching and learning for large numbers of students, a key strategy is extensive formative assessment with individualised feedback. The requirement of the Norms and Standards for Educators for 'ongoing developmental assessment' should be seen as a significant part of the teaching and learning strategy.

Implications for the evaluation of assessment in distance teacher education programmes

What should evaluators be looking for in the evaluation of the assessment practices in distance teacher education programmes?

An assessment design across the programme (rather than in each individual course or assignment) that will help the students develop applied and integrated competence.

Sufficient formative assessment with substantial individualised feedback to facilitate the gradual process of developing competence.

Evidence that the programme is informed by the contexts of the teachers it serves and conducts sufficient structured school-based observation to evaluate the extent to which it is developing teachers' applied competence.

Notes

1. Department of Education, 1998, Norms and Standards for Educators, Technical Committee on the Revision of Norms and Standards for Educators, Department of Education, Pretoria.

2. Description of purpose of project taken from: Musker, Paul, 1999, Educator Development Support Project: Final Report, Paul Musker and Associates for the Joint Education Trust and the Department of Education

3. Interview data from EDS Case Study Report

4. From Pilot EDS Case Study Report

5. Programme documentation data from EDS Case Study Report

7. Interview data from EDS Case Study Report

8. Interview data from EDS Case Study Report

9. Musker, Paul, 1999, Educator Development Support Project: Final Report, Paul Musker and Associates for the Joint Education Trust and the Department of Education

10. SAIDE, 1998, Strategies for the Design and Delivery of Quality Teacher Education at a Distance: A Case Study of the Further Diploma, English Language Teaching, University of the Witwatersrand, President's Education Initiative and Joint Education Trust

| South Africa | Contents | ||

South

African Institute for Distance Education |

|||